When can I have an EV?

Happy Monday/Tuesday! To readers who have stuck around, thank you; to new subscribers, welcome! 😊

Last Dispatch, we dipped into the ocean of renewable energy related questions, showing how a renewable energy grid can be a reliable one. We’ll soon return to that topic, looking into what it will take to deploy renewables at the rate required to keep net zero by 2050 within reach. ☀️

But for now, a brief interlude to tackle a topic of interest to anyone with a driver’s licence: when can I have an electric vehicle?

Why we need EVs on the road 🚙⚡️

EVs are key to reducing global emissions.

Transport contributes around a quarter of global CO2 emissions, roughly half of which comes from passenger vehicles. That’s a big chunk of emissions we can mitigate using existing technology: EVs.

Of course, running an EV isn’t entirely emissions free. For as long as there’s coal and gas in the electricity grid, EVs will be indirectly responsible for some electricity emissions.

Additionally, mining the metals required for an EV battery is emissions-intensive.

But even taking both factors into account, studies have shown again and again that EVs are still much better in emissions terms than their petrol-fuelled counterparts. 👍

Getting more EVs on the road quickly is key 🔑

It takes around 20 years for the global car fleet to turn over (think about how long your parents have had the family car), so even if 50 percent of cars sold in 2035 are electric, 70 percent of cars on the road could still be burning fossil fuels.

This emissions ‘lag’ highlights the importance of accelerating EV uptake now. To meet net zero by 2050, 60 percent of new vehicle sales should be electric in 2030, and all passenger vehicle sales should be electric by 2035.

Global state of play 🏈🏉

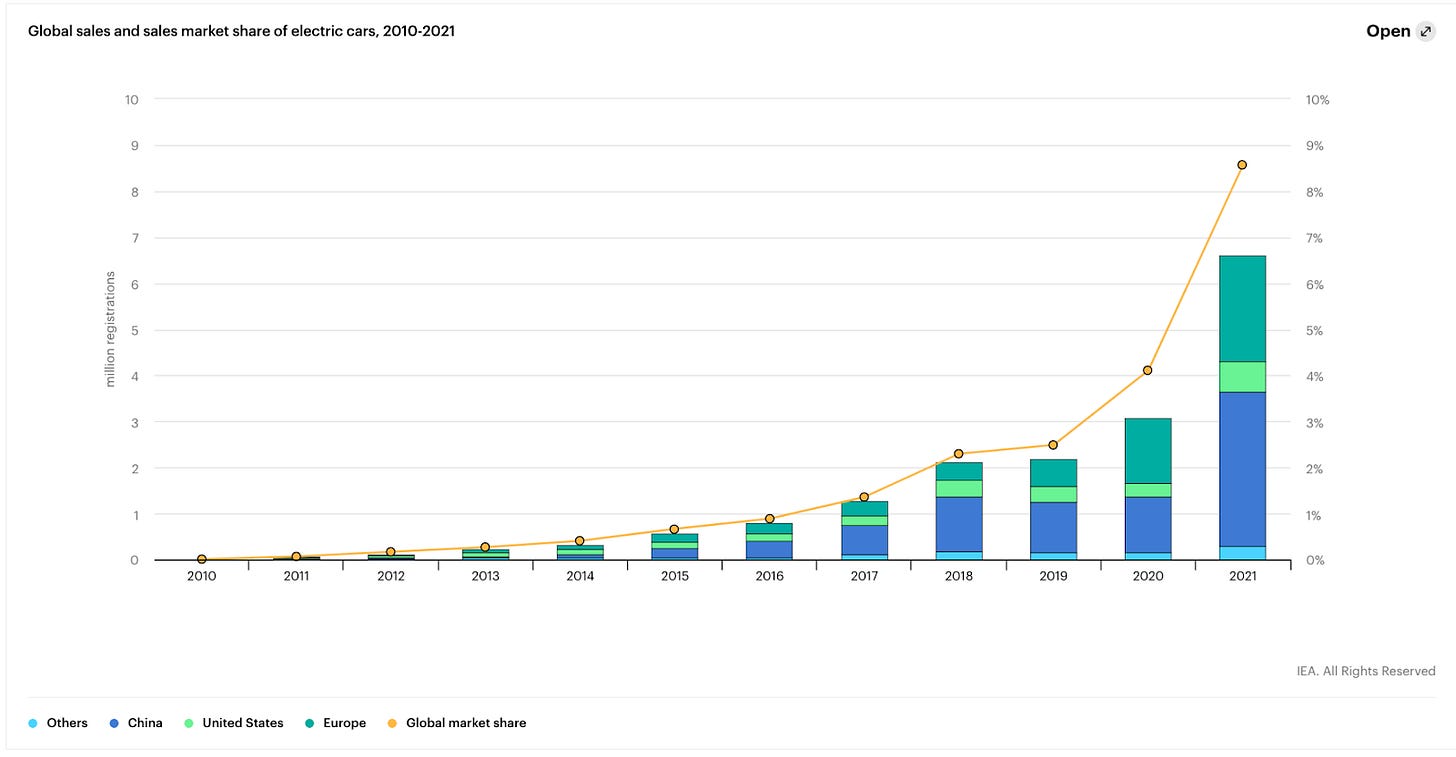

In 2021, around 9 percent of global car sales were EVs. That’s more than triple their 2.5 percent share in 2019, and 50 times the 130,000 EVs sold in 2012.

This impressive global growth rate is underpinned by a few higher performers. China, Europe, and the US account for 90 percent of EV sales but only two thirds of the global car market. 🇨🇳🇪🇺🇺🇸

More EVs were sold in China in 2021 than in the entire world in 2020. 15 percent of China’s car sales were electric last year.

EV share also climbed in Europe and the US – to 17 percent and 4.5 percent of new car sales, respectively.

In other major and growing car markets, like India, Brazil and Indonesia, EV share remains below one percent, according to the International Energy Agency. Australian EV purchases are climbing, but only just hit two percent.

To meet our climate goals, leading markets need to build momentum, and laggards need to pick up their game.

Source: International Energy Agency

I want to help. But I can’t afford an EV! 💰

EV battery costs (the main driver of the car’s price tag) are rapidly declining, and have fallen by almost 90 percent since 2010. But the upfront cost of an EV is still higher than the equivalent petrol or diesel-fuelled car (which is called an internal combustion engine or ICE vehicle in the industry). 💵 💶 💷 💴

In some markets, studies show the total cost of ownership is already less for EVs than ICE vehicles, simply because they’re much cheaper to run over time, even if the sticker price is higher. That’s great news for people who can afford to pay more now in return for savings over time – but not everyone is in that position.

You and I can’t change the price of an EV. That’s why …

Source: GIPHY

Many experts agree that without government intervention, the global EV switch won’t happen quickly enough. Markets with high EV uptake (think China, Norway, California, and Germany) have one thing in common: good public policy. 📝📊

By stimulating demand for EVs on the consumer side, and incentivising carmakers to increase their electric offering on the producer side, governments can have a meaningful impact on vehicle electrification. And the more EVs we make, the better we get at it, bringing down costs further. 🧑🏭

There are a number of levers governments can pull to increase EV uptake, including:

Vehicle emissions standards. These generally require carmakers to keep their entire product offering below a certain emissions threshold (basically, if they sell a car that emits above the threshold, it must be ‘cancelled out’ with a low or zero emissions car). Emissions limits can be ratcheted down over time, ideally to zero by 2035, when most or all cars on the market should be electric.

Unfun fact: Australia is one of the few developed economies without a legally binding vehicle emissions standard. The US has regulated vehicle emissions since the 1970s, China since 2004, and Europe since 2009. 👩⚖️

Fun fact: Regulating vehicle emissions also results in significant health savings. A 2018 study from researchers at the Universities of Bath and Oxford estimated vehicle pollution costs the UK health system around £6 billion per year. 🏥

Subsidies and tax rebates. They can make EVs more affordable for consumers, especially in the early stages of EV deployment, and as the market matures, governments can reduce and phase them out. 💰

For example, in the US, a Nissan Leaf EV starts around USD$27,400, but with the federal EV credit of up to $7,500, that could drop to $19,900. Several Australian states have introduced EV subsidies.

Phase-out dates for ICE vehicle sales. These send a signal to carmakers to ramp up their electric offering. In the last two years, there’s been an explosion in announced phase-out dates – e.g. 2035 in Canada and California, 2030 in the UK, and 2025 in Norway. ⛽️🚫

Fun fact: Automakers have followed suit, announcing electrification targets for their own offerings – Audi, Fiat and Volvo have announced they’ll sell a fully electric offering by 2030, while GM is targeting 2035. Ford, Hyundai and Volkswagen have ICE phase-out targets for Europe.

What if my government won’t do any of the above?

To some extent, countries without friendly EV policies will “free ride” on developments in other countries. 🏇

But the rollout of EVs will lag in those places. Manufacturers already prioritise getting EVs to markets with policy incentives in place.

For example, Volkswagen has delayed the delivery of new EV models to Australia, claiming the absence of a binding emissions standard means it won’t send zero emissions cars here first. With limited stock, it makes financial sense to sell EVs to markets that require a lower emissions fleet. Hyundai is in a similar boat.

Countries with fewer incentives and regulations won’t have as much choice when it comes to EV models, at least in the short to medium term, and risk becoming a dumping ground for older cars. According to Australian EV website The Driven, Germany and New Zealand (which both have emissions standards and subsidies for EVs) have over 100 models and 40 models available respectively, while Australia’s options number in the mid-30s (many at the luxury end). 🚗 🚙 🏎

The moral of the story is: your quickest pathway to EV ownership may be voting in a government with good EV policies. 🗳

Some of you might be wondering whether an EV is any use at all if you don’t know where you’ll charge it, or if you’ll be able to take it camping. We’ll cover EV charging (like who’s going to build the infrastructure and what it means for the electricity system) in a second EV Dispatch.

Topical island 🏝

Governments have their eye on green-washers (companies that exaggerate their environmental credentials):

On April 25, the UK Treasury announced a new taskforce to draft rules requiring financial firms and listed companies to publish detailed plans for their transition to net zero.

This comes just weeks after the US Wall Street regulator, the Securities Exchange Commission (SEC), proposed new rules requiring companies to more rigorously disclose climate risk to investors.

The Conversation has a good explainer here.

What in the world 🙊

A quick plug for my two favourite EVs:

The Rivian R1T electric pick-up truck, now priced at around USD$79,000. The largest model has a range of 640 km. It can tow around 5,000 kg (which drops its range to half), and charge about 225 km in 20 minutes with a fast-charger. Watch it playing in the snow here.

Source: Rivian

The Wuling Hongguan Mini EV – a Chinese car with a starting price of USD$4,200. It’s so cheap and small it doesn’t even qualify for China’s EV subsidies but is still one of the country’s best sellers.

Source: speedster.news

Tips? Questions ? Feedback?👩💻 —> isabella.borshoff@gmail.com

(I’d love to hear what topics you think would be useful in a future newsletter, or any follow up questions you have on this one!)